Coincidentally I was reading We Need to Talk About Kevin by Lionel Shriver when the Florida school shooting took place killing 17. It was a riveting read about a 17 year old boy who kills 9 people in his school and more so as I longed to understand what goes on in the mind of any young person capable of committing these atrocious acts. In the book, Kevin’s mother (the narrator) also struggles to understand why her son meticulously planned and carried out the murder of 8 school companions and one teacher. I will not spoil the book for anyone who wishes to read it and, in spite of what I considered an unnecessarily gruesome end, it was well worth the read.

As with everyone I know, I was horrified not only by the Florida killings, but with the printed fact that by the 15th of February there had been 18 school shootings in the United States[1]. That’s one shooting every two and a half days, every 36 hours. No, mistake: there are 13 days (weekends and the 1st of January) where there was no school, so it was 18 shootings in 34 days, or a shooting every 1.8 days. As The Guardian states in the note below, there were a couple of accidents, some incidents with no deaths, and two suicides but none the less, there were 18 gun related incidents in schools in the first 34 working days of 2018.

As if this were not bad enough, I then heard President Trump (or The Donald as Obama called him) say that the problem was that schools were gun-free zones (not that kids could buy or get a hold of automatic and semi-automatic weapons) and that the solution was to arm the teachers[2], a proposal that shouldn’t even merit comment, much less consideration, an opinion I voiced to a group of friends during market day in Salies. I was surprised to find that one of the ladies, though claiming that semi and automatic weapons should be banned, considered that having a gun was a necessary defense. This made me think of my father and remember an incident that taught me a lot about guns when I was young.

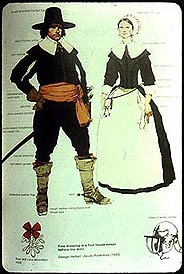

First some background. My father was a hunter (the picture on the left depicts him at 18, in Spain, 1920) and, as such, owned a good amount of shotguns which he kept under lock and key in a gun cabinet. Everything I know about guns I learned from him. Even as a child I was taught that you never, EVER, point a gun –even a toy gun, even a water pistol- directly at another person. When I asked my father why he didn’t buy himself a pistol, he said that he had shotguns because they were for hunting; pistols, and most other weapons were for shooting people and he had long ago decided that he never wanted to kill any other human being (he had done his military service during the Rif war in Africa and, from what I have read about it, there were atrocities committed on both sides); that –according to him- was the reason he had not gone back to Spain when the Civil War broke out for he would have been expected –as a member of the Spanish nobility- to lead troops into battle.

First some background. My father was a hunter (the picture on the left depicts him at 18, in Spain, 1920) and, as such, owned a good amount of shotguns which he kept under lock and key in a gun cabinet. Everything I know about guns I learned from him. Even as a child I was taught that you never, EVER, point a gun –even a toy gun, even a water pistol- directly at another person. When I asked my father why he didn’t buy himself a pistol, he said that he had shotguns because they were for hunting; pistols, and most other weapons were for shooting people and he had long ago decided that he never wanted to kill any other human being (he had done his military service during the Rif war in Africa and, from what I have read about it, there were atrocities committed on both sides); that –according to him- was the reason he had not gone back to Spain when the Civil War broke out for he would have been expected –as a member of the Spanish nobility- to lead troops into battle.

When I was around the age of 13, my father began to show me how and how not to handle a shotgun. I was taught that the moment the gun was handed to you, you break it open and check the barrels to see if it is loaded; that you never walk with a loaded gun even if you have it open (his best friend had lost an arm by tripping while walking with an open, loaded gun); that the safety should be on at all times until the moment you plan to shoot your prey. He showed me how to clean a gun after using it, how to aim ahead of a flying prey so that the shot and the bird would cross paths. He took me to shoot skeet at the gun club and let me practice until I was pretty good at it. Then he took me duck  hunting, in Acapulco, out at the Lagoon of ‘Tres Palos’ (Three Sticks) where we stood, at the break of dawn, up to the knees in swamp water, hidden by the marsh grasses, waiting for the ducks to fly over. I remember feeling very important to have been included in the hunting expedition (my mother had preferred to stay home in bed and was happy to have me as a stand-in) although I don’t know if I shot any duck on that first time. Neither do I remember how often I went with my father. Actually I only have two clear memories of these experiences: the first, feeling things crawling up my legs from the swampy water (and discovering later that it was nothing more than the air bubbles from my sneakers) and the time I shot and wounded a duck. The poor animal dropped to the water well within my reach and I could see it fluttering helplessly. From watching my father, I knew that it was my obligation to wring the creature’s neck in order to end the suffering I myself had caused it. So I waded out to where the bird lay and took it gently by the head with my right hand. Then, trying not to look into its eyes which were still open and alive and attempting to kill it without causing it harm, I gave it a couple of soft swirls. I can still feel today the warmth of its body, the life still present there. I was heartbroken, I hated myself and I just wanted the damn bird to die so I could stop suffering myself. It did not oblige under the gentleness of my feeble attempts. So after three half-hearted swings and seeing that the duck was still flapping around suffering, I could stand it no longer. I plunged the feathery body into the water and put my heavy cartridge box on top of it so that it finally drowned to death. I realized in that moment that I was not capable of killing an animal and I have never been hunting since.

hunting, in Acapulco, out at the Lagoon of ‘Tres Palos’ (Three Sticks) where we stood, at the break of dawn, up to the knees in swamp water, hidden by the marsh grasses, waiting for the ducks to fly over. I remember feeling very important to have been included in the hunting expedition (my mother had preferred to stay home in bed and was happy to have me as a stand-in) although I don’t know if I shot any duck on that first time. Neither do I remember how often I went with my father. Actually I only have two clear memories of these experiences: the first, feeling things crawling up my legs from the swampy water (and discovering later that it was nothing more than the air bubbles from my sneakers) and the time I shot and wounded a duck. The poor animal dropped to the water well within my reach and I could see it fluttering helplessly. From watching my father, I knew that it was my obligation to wring the creature’s neck in order to end the suffering I myself had caused it. So I waded out to where the bird lay and took it gently by the head with my right hand. Then, trying not to look into its eyes which were still open and alive and attempting to kill it without causing it harm, I gave it a couple of soft swirls. I can still feel today the warmth of its body, the life still present there. I was heartbroken, I hated myself and I just wanted the damn bird to die so I could stop suffering myself. It did not oblige under the gentleness of my feeble attempts. So after three half-hearted swings and seeing that the duck was still flapping around suffering, I could stand it no longer. I plunged the feathery body into the water and put my heavy cartridge box on top of it so that it finally drowned to death. I realized in that moment that I was not capable of killing an animal and I have never been hunting since.

However, the incident that taught me the truth about guns took place a year of two later. Our house in Mexico City –as most of the houses there- had a flat roof where we hung the laundry and had a storeroom. Late one night, after we had all gone to bed, my father heard footsteps on the roof and realized that someone had managed to climb up there and was walking around. As my mother told the story later, my father grabbed a broomstick and went up to the roof to face the invader. She was laughing and my father was right there eating breakfast so it was obvious the story had a good ending, but I was shocked.

However, the incident that taught me the truth about guns took place a year of two later. Our house in Mexico City –as most of the houses there- had a flat roof where we hung the laundry and had a storeroom. Late one night, after we had all gone to bed, my father heard footsteps on the roof and realized that someone had managed to climb up there and was walking around. As my mother told the story later, my father grabbed a broomstick and went up to the roof to face the invader. She was laughing and my father was right there eating breakfast so it was obvious the story had a good ending, but I was shocked.

“Why didn’t you take one of your shotguns?” I queried, thinking how ridiculous and helpless a broomstick must have looked to the invader. “Supposing he had had a gun?”

“Well,” my father explained, “if he had had a gun, he obviously would have been more than prepared to use it, something that for me would have been difficult if not impossible; so if I had appeared with a gun he might have shot me right off while I considered the possibility of doing the same. A person who breaks into a house with a gun is prepared to use it; I was not. It was safer to go up without a gun if you know you are probably going to think twice before pulling the trigger.”

I understood perfectly: I couldn’t even wring the neck of a dying duck to stop its suffering! So, I ask myself or anyone else who will listen, how many teachers are prepared to pull out a gun and shoot a student before he sprays everyone in the classroom with automatic fire power? It’s ridiculous! Even if the teacher is trained and manages to extract his/her gun from its concealment, aim at the student and pull the trigger, the possibility of landing a deterring shot before the other responds in kind is minimal. And then we have to think how many teachers would be able to do this and how can we be sure that the classroom to be shot up is one with a gun-toting teacher? My history class was taught by a Miss Hunter who –if I remember correctly- was a small, aged lady with white hair and glasses. I just can’t imagine her pulling out a Smith and Wesson from her girdle and shooting our aspiring high school killer before saying calmly to the class: “Please open your History books to page 347 where we left off last Friday and commence reading, and, Ralph, would you mind removing that trash from the doorway and depositing it in the Principal’s office.”

The basic argument against gun control runs to some version of the following: “With gun control, the good people will be forced to give up their guns while the baddies will continue to have them; we will be defenseless”. Nothing is farther from the truth, as my father well understood and showed me with his brave example. If someone armed enters to rob my house, he/she probably does not mean to kill me, just to take what he/she wants and depart. He/she will only shoot me if I threaten to shoot him/her. If, on the other hand, someone wants to kill me, they will undoubtedly do it while I am walking down the street unarmed, or driving by in a car unarmed and not while I am in my own home where I might have a weapon. Therefore, gun control might actually save my life, not put it in danger.

The mostly ‘kids’ who shoot up schools are not hardened criminals; they are usually ordinary –sometimes mentally or emotionally disturbed (not ‘sicko’ as Trump said)- kids. Gun control would make it more difficult for these unfortunates (yes, they are as unfortunate or perhaps more so than the ones they kill) to obtain weapons, especially automatic weapons. It is much more difficult to kill 17 people shooting them one by one, than it is spraying them with a hail of bullets without even having to aim.

As I am not a hunter, personally I have no use for a gun in the house; I know I would be absolutely incapable of using it. I have proof, for when I was kidnapped, many years ago in Mexico City, I found myself trying to figure out a way to escape. One day, the kidnappers left an empty bottle of wine in my room and I thought to myself that I could use it to hit my guard over the head the next time he came in and make a break for it. Immediately I realized I would try to do it gently so as not to hurt him (just like the poor duck) and that would have me ending up as the object of his wrath. Fortunately, the police did the job for me and I was rescued.[3]

So if you ask me –and nobody has- I’d say “not more guns, not less guns, but NO GUNS is the only solution.”

[1] In all, guns have been fired on school property in the US at least 18 times so far this year, according to incidents tracked by Everytown for Gun Safety, a gun control group. In eight of these cases, a gun was fired on school property, but no one was injured. Another two incidents were gun suicides, claiming the lives of one student and one adult on school property. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/feb/14/school-shootings-in-america-2018-how-many-so-far

[2] Some gun rights advocates have pushed to expand gun-carrying in schools further. Andrew McDaniel, a state legislator in Missouri who introduced legislation last year to make it easier to carry guns in schools, told the Guardian that, in rural schools where it might take 20 or 30 minutes for law enforcement to respond to a school shooting in progress, it made sense to have other armed citizens ready to step in. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/feb/14/school-shootings-in-america-2018-how-many-so-far

[3] The book I wrote about this incident is called Once días… y algo más and is available on Amazon; the translation into English, Eleven Days, is out of print and 2nd hand copies are quite expensive I believe.

–doubly so, because my husband couldn’t understand what I was so angry about- said a couple of nasty things in a loud voice and stomped off to the bedroom. The thought was: ‘How can she be so cruel’, obviously to me. That scene alone sufficed for years to prove to me how unloving my mother was which, of course, was one of the reasons I was so messed up.

–doubly so, because my husband couldn’t understand what I was so angry about- said a couple of nasty things in a loud voice and stomped off to the bedroom. The thought was: ‘How can she be so cruel’, obviously to me. That scene alone sufficed for years to prove to me how unloving my mother was which, of course, was one of the reasons I was so messed up. realized I had done the best I knew how to do with the information I had at the moment and that now, with new information, I would hopefully not repeat the mistake. Slate wiped clean.

realized I had done the best I knew how to do with the information I had at the moment and that now, with new information, I would hopefully not repeat the mistake. Slate wiped clean. As far as the group went, there was only one person (whom I will call our local Drama Queen because she is always in a state of righteous anger about something somewhere she has found wrong) in the Café and I walked over to say hello. Before I could reach her, she swung around on her barstool and told me she was furious with me because I had fought with the other member of the group and therefore she –the person I had fought with- wouldn’t be coming to the coffee group any more as long as I was there, and therefore the Drama Queen would never see her again. I politely, but firmly, set the story right (I did not fight with her, I made a mistake and she was apparently hurt by it) and told her not to worry, that it would be me quitting the group so the other friend could come. I realized, in that moment, that I had made a decision.

As far as the group went, there was only one person (whom I will call our local Drama Queen because she is always in a state of righteous anger about something somewhere she has found wrong) in the Café and I walked over to say hello. Before I could reach her, she swung around on her barstool and told me she was furious with me because I had fought with the other member of the group and therefore she –the person I had fought with- wouldn’t be coming to the coffee group any more as long as I was there, and therefore the Drama Queen would never see her again. I politely, but firmly, set the story right (I did not fight with her, I made a mistake and she was apparently hurt by it) and told her not to worry, that it would be me quitting the group so the other friend could come. I realized, in that moment, that I had made a decision. Strangely, as I walked home, the thought of not going to the café every morning for coffee didn’t weigh me down; on the contrary, I felt lighter. Inside, there was a conviction that the Universe never closes a door without opening a window, and all of a sudden I began looking forward to what might come next. Yes, during the afternoon, I had a couple of down-thoughts (I won’t have the group to buy presents for when I travel any more, and there will be no birthday celebration for me on the 1st of August this year) and a slight feeling of loss swept through my chest thinking of the friend who will not forgive, but on the whole I felt pretty good. During the afternoon, I wrote to the coffee group and explained the situation without going into details, and announced that I would be retiring from the group out of respect for the ‘injured’ party who had been there long before me.

Strangely, as I walked home, the thought of not going to the café every morning for coffee didn’t weigh me down; on the contrary, I felt lighter. Inside, there was a conviction that the Universe never closes a door without opening a window, and all of a sudden I began looking forward to what might come next. Yes, during the afternoon, I had a couple of down-thoughts (I won’t have the group to buy presents for when I travel any more, and there will be no birthday celebration for me on the 1st of August this year) and a slight feeling of loss swept through my chest thinking of the friend who will not forgive, but on the whole I felt pretty good. During the afternoon, I wrote to the coffee group and explained the situation without going into details, and announced that I would be retiring from the group out of respect for the ‘injured’ party who had been there long before me. This morning I went to another café (where the coffee is slightly more expensive but much, much better) and had a jolly conversation with a woman who was visiting from a nearby village (in French!). Then at noon, I met the Artist lady and her friends, spent a delightful two hours and had a delicious lunch. C’est la vie, what to do, that’s life!

This morning I went to another café (where the coffee is slightly more expensive but much, much better) and had a jolly conversation with a woman who was visiting from a nearby village (in French!). Then at noon, I met the Artist lady and her friends, spent a delightful two hours and had a delicious lunch. C’est la vie, what to do, that’s life! A friend asked me today how I had felt about giving up my American citizenship and if it hadn’t been a hard thing to do. I said “no”, that given my rootless upbringing it made little difference. At nine years old, when I was just beginning to discover that I belonged to something much larger than my immediate family, we moved to Mexico and everything changed. My mother stopped cooking dinner for the family and the children (my brother and I) were served supper in the kitchen by and with the maids who spoke Spanish, a language I still had to learn. The acres and acres of fields and woodlands that surrounded our house in New Canaan became a fenced in garden with nothing but flowers and grass and a few trees. Gone were the vegetable patch and the field with wild blueberries; gone the endless woods and the long walks with my father; gone were the tractor and hay rides in the autumn… as a matter of fact, gone were the spring, the summer, the autumn and especially the winter. Instead, there was a dry season from October to June and a wet one from July through September. There was no snow except on the peaks of the (then) visible volcanos, Iztaccihuatl

A friend asked me today how I had felt about giving up my American citizenship and if it hadn’t been a hard thing to do. I said “no”, that given my rootless upbringing it made little difference. At nine years old, when I was just beginning to discover that I belonged to something much larger than my immediate family, we moved to Mexico and everything changed. My mother stopped cooking dinner for the family and the children (my brother and I) were served supper in the kitchen by and with the maids who spoke Spanish, a language I still had to learn. The acres and acres of fields and woodlands that surrounded our house in New Canaan became a fenced in garden with nothing but flowers and grass and a few trees. Gone were the vegetable patch and the field with wild blueberries; gone the endless woods and the long walks with my father; gone were the tractor and hay rides in the autumn… as a matter of fact, gone were the spring, the summer, the autumn and especially the winter. Instead, there was a dry season from October to June and a wet one from July through September. There was no snow except on the peaks of the (then) visible volcanos, Iztaccihuatl plants generally flowered all year around but never with the magical profusion of a New England spring. Even the school year was then different as at that time, in Mexico, the long vacations were over Christmas (to take advantage of the sunny dry season) and school continued during the summer (when rain made everyone stay indoors anyway)

plants generally flowered all year around but never with the magical profusion of a New England spring. Even the school year was then different as at that time, in Mexico, the long vacations were over Christmas (to take advantage of the sunny dry season) and school continued during the summer (when rain made everyone stay indoors anyway) to pick up a comic of Memín Pinguin or Kaliman which is what Mexicans were reading at the time. In other words, it was like living on a small and distant island belonging to the US but not really America. Every time I went to the States (as we called it) I felt like a second-class; each visit showed me more how out of real American life I was and how different I was. My cousins would introduce me as their “Mexican” relative and ask me to speak Spanish while they pretended to understand what I was saying and showed off in front of their friends. They had toys I had never heard of, read comic books that weren’t sold in Mexico and shared a common cultural language with their friends that was as foreign to me as Spanish was to them.

to pick up a comic of Memín Pinguin or Kaliman which is what Mexicans were reading at the time. In other words, it was like living on a small and distant island belonging to the US but not really America. Every time I went to the States (as we called it) I felt like a second-class; each visit showed me more how out of real American life I was and how different I was. My cousins would introduce me as their “Mexican” relative and ask me to speak Spanish while they pretended to understand what I was saying and showed off in front of their friends. They had toys I had never heard of, read comic books that weren’t sold in Mexico and shared a common cultural language with their friends that was as foreign to me as Spanish was to them. immediately with something children don’t see much of in the USA: a marked class difference. As a matter of fact, my contact with Mexicans was seldom as friends. The closest were the maids, separated from me by their language, the color of their skin, their age and their maid’s uniforms… in other words, their position in the household. Then there were the lecherous men who made obscene and salacious remarks with words I had never heard before as I walked by. There was the kind gentleman, who had the paper store where I went often to buy paper dolls and crayons and notebooks and pencils, and the girls at the checkout counter in the supermarket (but you never got to know them). There were the sad looking men who put on worn out uniforms and tried to direct the parking in town or at the market. My mother would always get mad at them because “they didn’t help, just blew their whistles but never picked up a bag for you”. They were commonly called “pesómanos” and it was generally expected that you would give them a “peso”

immediately with something children don’t see much of in the USA: a marked class difference. As a matter of fact, my contact with Mexicans was seldom as friends. The closest were the maids, separated from me by their language, the color of their skin, their age and their maid’s uniforms… in other words, their position in the household. Then there were the lecherous men who made obscene and salacious remarks with words I had never heard before as I walked by. There was the kind gentleman, who had the paper store where I went often to buy paper dolls and crayons and notebooks and pencils, and the girls at the checkout counter in the supermarket (but you never got to know them). There were the sad looking men who put on worn out uniforms and tried to direct the parking in town or at the market. My mother would always get mad at them because “they didn’t help, just blew their whistles but never picked up a bag for you”. They were commonly called “pesómanos” and it was generally expected that you would give them a “peso” in the office who were very nice. But they weren’t people you would invite to dinner at your house or whose children would come over to play. A few of my mother’s friends that she played golf with were Mexican, but they all spoke English and I, of course, knew them only slightly as “Mom’s friends”.

in the office who were very nice. But they weren’t people you would invite to dinner at your house or whose children would come over to play. A few of my mother’s friends that she played golf with were Mexican, but they all spoke English and I, of course, knew them only slightly as “Mom’s friends”. to which I was foreign. I remember a strange feeling of not belonging, not belonging anywhere. In Mexico I was not a Mexican, I was not even a Mexican-American along with my ex-pat friends; and in the United States, I was an American by passport only.

to which I was foreign. I remember a strange feeling of not belonging, not belonging anywhere. In Mexico I was not a Mexican, I was not even a Mexican-American along with my ex-pat friends; and in the United States, I was an American by passport only. was finishing his doctor’s degree. Not one of their customs and habits were anything like those of my family. It was, so to speak, deep-Mexico. I was attracted to the size and closeness of his family although I would soon discover that his father was an alcoholic and went on periodic binges. His mother was extremely overweight (110 kilos) but a kind and simple woman whom I grew to love. His family was warm and close in ways that mine had never been and I felt very welcomed; his father forbade the use of the derogatory term “gringa” around his house from the first time he met me. I began to feel that I was accepted and therefore that I belonged in this family.

was finishing his doctor’s degree. Not one of their customs and habits were anything like those of my family. It was, so to speak, deep-Mexico. I was attracted to the size and closeness of his family although I would soon discover that his father was an alcoholic and went on periodic binges. His mother was extremely overweight (110 kilos) but a kind and simple woman whom I grew to love. His family was warm and close in ways that mine had never been and I felt very welcomed; his father forbade the use of the derogatory term “gringa” around his house from the first time he met me. I began to feel that I was accepted and therefore that I belonged in this family. Spanish was a quick recipient of my rage. I had also gone through several years of psychoanalysis and become a recovering alcoholic.

Spanish was a quick recipient of my rage. I had also gone through several years of psychoanalysis and become a recovering alcoholic. There was only one thing to do: renounce my American citizenship and become Mexican, and for that, it turned out, I had a slight advantage. As I had left the United States as a child and never legally worked there I did not have a Social Security number or a Taxpayer number or anything that even closely resembled it. Even though there was always the chance that, when they checked my “record”, not finding me would be as damning as having purposely not paid taxes, but I could see no other way to solve the problem. I know that ignorance is not considered innocence under the law, but it sure felt enough like it for me. So I was finally going to make the ‘roots’ I had put down legal.

There was only one thing to do: renounce my American citizenship and become Mexican, and for that, it turned out, I had a slight advantage. As I had left the United States as a child and never legally worked there I did not have a Social Security number or a Taxpayer number or anything that even closely resembled it. Even though there was always the chance that, when they checked my “record”, not finding me would be as damning as having purposely not paid taxes, but I could see no other way to solve the problem. I know that ignorance is not considered innocence under the law, but it sure felt enough like it for me. So I was finally going to make the ‘roots’ I had put down legal.

mother, in Reno Nevada the 13th of June, 1941 and only one hour after they had both obtained “quickie” divorces from their respective spouses. Seeing as she had been a single woman only for the last 60 minutes, my mother apparently had no ID in her maiden name, Cook, and thus was married to my father using her married name, Wasey. Therefore, my mother being Elizabeth Cook while my father married Elizabeth Wasey I could see the difficulty of having to try to explain this to the third level bureaucrat who was going to issue my Spanish birth certificate. So, as I sat in the grey office, in front of the grey representative of the Spanish government who was filling out my papers, I was fully prepared to accept my bastardhood. When she asked if I was sure they were never married, I lied and answered immediately that I was. She then informed me that, as I was an illegitimate child and this would be visible on the birth certificate, I would have to come personally to pick it up.

mother, in Reno Nevada the 13th of June, 1941 and only one hour after they had both obtained “quickie” divorces from their respective spouses. Seeing as she had been a single woman only for the last 60 minutes, my mother apparently had no ID in her maiden name, Cook, and thus was married to my father using her married name, Wasey. Therefore, my mother being Elizabeth Cook while my father married Elizabeth Wasey I could see the difficulty of having to try to explain this to the third level bureaucrat who was going to issue my Spanish birth certificate. So, as I sat in the grey office, in front of the grey representative of the Spanish government who was filling out my papers, I was fully prepared to accept my bastardhood. When she asked if I was sure they were never married, I lied and answered immediately that I was. She then informed me that, as I was an illegitimate child and this would be visible on the birth certificate, I would have to come personally to pick it up.

Interestingly enough, I didn’t even realize I had a bucket list until I started checking things off. I guess one of the first, if not the very first, was living in Madrid. When I thought about it before it happened, my response was: “Well, I guess it won’t be in this lifetime.” But, it happened when I least expected. I can’t remember what the second was, but it will come back… or not. The third was going to Machu Picchu; I was certain that I would not do it in this lifetime. I was getting too old to take the altitude and then there was no one to go with until, suddenly, when my son turned 50, it occurred to me that I could give him the trip as a birthday present (birthday present for me too, I guess), so we went to Machu Picchu: me, my son and my lovely daughter-in-law. Once the way to do it was discovered, the fourth item on the list was easy. The Galapagos Islands were seen and enjoyed with the most wonderful company of my daughter, my son and once more his wife.

Interestingly enough, I didn’t even realize I had a bucket list until I started checking things off. I guess one of the first, if not the very first, was living in Madrid. When I thought about it before it happened, my response was: “Well, I guess it won’t be in this lifetime.” But, it happened when I least expected. I can’t remember what the second was, but it will come back… or not. The third was going to Machu Picchu; I was certain that I would not do it in this lifetime. I was getting too old to take the altitude and then there was no one to go with until, suddenly, when my son turned 50, it occurred to me that I could give him the trip as a birthday present (birthday present for me too, I guess), so we went to Machu Picchu: me, my son and my lovely daughter-in-law. Once the way to do it was discovered, the fourth item on the list was easy. The Galapagos Islands were seen and enjoyed with the most wonderful company of my daughter, my son and once more his wife. things in life. I opened an email from my English friend, Tamara, and it was an invitation to Kalikalos, in Greece, for a workshop of the Byron Katie Work. I had received that invitation several times before because Tamara does this workshop every year, but suddenly something in my body said “yes”, and I immediately wrote my friend an e-mail asking if she would accept me as a helper or staff. She agreed, I got my tickets and on the 25th of August, flew to Thessaloniki via Athens. There we were to meet in a hotel in order to drive to Mount Pelion the following morning.

things in life. I opened an email from my English friend, Tamara, and it was an invitation to Kalikalos, in Greece, for a workshop of the Byron Katie Work. I had received that invitation several times before because Tamara does this workshop every year, but suddenly something in my body said “yes”, and I immediately wrote my friend an e-mail asking if she would accept me as a helper or staff. She agreed, I got my tickets and on the 25th of August, flew to Thessaloniki via Athens. There we were to meet in a hotel in order to drive to Mount Pelion the following morning. Thessaloniki overlooks a bay in the Aegean Sea so that evening I sat on the porch of the hotel restaurant enjoying a Greek salad and finding it hard to believe that I was actually in Greece. The night sported a sparkling necklace of multicolored lights adorning the land-face and separating it from the black bodice of the bay. From pool-side speakers Latin-American music permeated the atmosphere mingling with laughter and conversations at other tables. I might have just as well been in Las Brisas, overlooking the Acapulco Bay. Even the gentleness of the waiters and the hotel staff’s willingness to be of service reminded me of Mexico. I wondered if the rest of the trip was also going to be this sweet sliding into nostalgia.

Thessaloniki overlooks a bay in the Aegean Sea so that evening I sat on the porch of the hotel restaurant enjoying a Greek salad and finding it hard to believe that I was actually in Greece. The night sported a sparkling necklace of multicolored lights adorning the land-face and separating it from the black bodice of the bay. From pool-side speakers Latin-American music permeated the atmosphere mingling with laughter and conversations at other tables. I might have just as well been in Las Brisas, overlooking the Acapulco Bay. Even the gentleness of the waiters and the hotel staff’s willingness to be of service reminded me of Mexico. I wondered if the rest of the trip was also going to be this sweet sliding into nostalgia. Tamara arrived just before midnight and I was almost asleep so we didn’t talk that night. The following morning after a satisfying breakfast, we climbed into a small blue Fiat Panda, picked up two lady passengers who were also attending the workshop and set off down the modern highway towards our destination on Mount Pelion,

Tamara arrived just before midnight and I was almost asleep so we didn’t talk that night. The following morning after a satisfying breakfast, we climbed into a small blue Fiat Panda, picked up two lady passengers who were also attending the workshop and set off down the modern highway towards our destination on Mount Pelion,  a mountain forming a hook-like peninsula between the Pagasetic Gulf and the Aegean Sea on the southeastern rim of Thessaly in central Greece.

a mountain forming a hook-like peninsula between the Pagasetic Gulf and the Aegean Sea on the southeastern rim of Thessaly in central Greece. After driving past Mount Olympus we continued for hours on a straight motorway bordered by flat terrain, the unaesthetic forms of warehouses and the usual highway clutter; then we suddenly turned off onto a local road, passed the port city of Volos and began to climb. Immediately the landscape gave way to cliffs and lovely white and beige Greek houses huddled in the crevices and clinging to the mountain side like nesting doves. The road narrowed as it curved its way through township after

After driving past Mount Olympus we continued for hours on a straight motorway bordered by flat terrain, the unaesthetic forms of warehouses and the usual highway clutter; then we suddenly turned off onto a local road, passed the port city of Volos and began to climb. Immediately the landscape gave way to cliffs and lovely white and beige Greek houses huddled in the crevices and clinging to the mountain side like nesting doves. The road narrowed as it curved its way through township after  township, each offering its produce for passing tourists: pottery, basket ware, honey and marmalades; hats, beachwear and inflatables bursting with colorful temptation. Then the forest began to thicken and the road seemed to narrow even more, hemmed in by tall trunks and mountain on one side and deep crevices on the

township, each offering its produce for passing tourists: pottery, basket ware, honey and marmalades; hats, beachwear and inflatables bursting with colorful temptation. Then the forest began to thicken and the road seemed to narrow even more, hemmed in by tall trunks and mountain on one side and deep crevices on the other. Beech, oak, maple and chestnut trees competed with each other for room on the steep slopes, and stretched tall, harvesting their share of Greek sunshine. According to Wikipedia, the Pelion is considered one of the most beautiful mountains in Greece, and after driving up and down it various times, I can confirm that it is indeed beautiful. It is also a very popular tourist attraction, offering hiking trails, stone paths, springs and, of course, incredible coves and beaches, both sandy and pebbly, with the white, white stones that Greece is known for and that tourists like

other. Beech, oak, maple and chestnut trees competed with each other for room on the steep slopes, and stretched tall, harvesting their share of Greek sunshine. According to Wikipedia, the Pelion is considered one of the most beautiful mountains in Greece, and after driving up and down it various times, I can confirm that it is indeed beautiful. It is also a very popular tourist attraction, offering hiking trails, stone paths, springs and, of course, incredible coves and beaches, both sandy and pebbly, with the white, white stones that Greece is known for and that tourists like  myself collect to bring home and sport in our household flower pots. During the winter, the highest peaks gather a good covering of snow and two ski lifts take the enthusiasts up and down. So tourism is the livelihood of many mountain dwellers all year around.

myself collect to bring home and sport in our household flower pots. During the winter, the highest peaks gather a good covering of snow and two ski lifts take the enthusiasts up and down. So tourism is the livelihood of many mountain dwellers all year around. Mount Pelion took its name from the mythical king Peleus, father of Achilles and became the home of the Centaur, Chiron, tutor of many Greek heroes (Jason, Achilles, Theseus and Heracles). The symbol for Mount Pelion today is the centaur and this image can be found all over.

Mount Pelion took its name from the mythical king Peleus, father of Achilles and became the home of the Centaur, Chiron, tutor of many Greek heroes (Jason, Achilles, Theseus and Heracles). The symbol for Mount Pelion today is the centaur and this image can be found all over. We climbed up to 500 meters above sea level to a lovely little village called Kissos. The center of town consists of three enormous plane trees, a small church, several restaurants, a few shops, a neighborhood supermarket and a pharmacy. Saturday night we were treated to the music from a Greek wedding held under one of the plane trees, to which possibly all the neighbors had been invited, because it went on until 4am. Sunday, it was the voice of the priest and his second in command singing the mass over loudspeakers so that everyone (not in the church) could, or was

We climbed up to 500 meters above sea level to a lovely little village called Kissos. The center of town consists of three enormous plane trees, a small church, several restaurants, a few shops, a neighborhood supermarket and a pharmacy. Saturday night we were treated to the music from a Greek wedding held under one of the plane trees, to which possibly all the neighbors had been invited, because it went on until 4am. Sunday, it was the voice of the priest and his second in command singing the mass over loudspeakers so that everyone (not in the church) could, or was  obliged to, tune in.

obliged to, tune in. workshop, a facial-lift massage, reflexology and guided hikes up and down the mountainside. We were all invited to make ourselves part of the community by helping in diverse chores throughout our stay: cooking, cleaning, keeping the gardens, etc. This insures that every meal becomes a communal affair with laughter and conversation all the way through. Dinner, which is the main meal, is preceded by forming a circle holding hands and listening while the cook-in-turn announces the evening’s fare and wishes everyone a healthy and happy meal. The clean-up crew gets to serve themselves first so that they may begin their duties as soon as they are finished. Every chore has a ‘focalizer’ and

workshop, a facial-lift massage, reflexology and guided hikes up and down the mountainside. We were all invited to make ourselves part of the community by helping in diverse chores throughout our stay: cooking, cleaning, keeping the gardens, etc. This insures that every meal becomes a communal affair with laughter and conversation all the way through. Dinner, which is the main meal, is preceded by forming a circle holding hands and listening while the cook-in-turn announces the evening’s fare and wishes everyone a healthy and happy meal. The clean-up crew gets to serve themselves first so that they may begin their duties as soon as they are finished. Every chore has a ‘focalizer’ and  several ‘helpers’ so the work is done rapidly and efficiently. The community is set up in May and lasts until October (

several ‘helpers’ so the work is done rapidly and efficiently. The community is set up in May and lasts until October ( favorite –as far as Greek food- was the tzatziki dip, made with yoghurt, cucumber, garlic and sometimes quite spicy. The fried cheese, which somebody raved about, was a bit like eating a tasty breaded piece of rubber, but the veggies were great: aubergine, zucchini, tomatoes and onions… my favorite, and quinoa –no matter how it’s made- I can just die for! All in all I loved Kalikalos and there was something about the whole atmosphere that just invited me to

favorite –as far as Greek food- was the tzatziki dip, made with yoghurt, cucumber, garlic and sometimes quite spicy. The fried cheese, which somebody raved about, was a bit like eating a tasty breaded piece of rubber, but the veggies were great: aubergine, zucchini, tomatoes and onions… my favorite, and quinoa –no matter how it’s made- I can just die for! All in all I loved Kalikalos and there was something about the whole atmosphere that just invited me to ‘space out’ which I did.

‘space out’ which I did.

The other day I sent my son some quotes –some very funny ones- that I had just discovered were things said by Yogi Berra, the baseball player. My son wrote back: You mean Yogi Bear, don’t you? My son is in his 50s (and that sounds horrible because it puts me 20-some years ahead of him). I wrote back and explained that, no, I did not mean Yogi Bear. He had never heard of Yogi Berra.

The other day I sent my son some quotes –some very funny ones- that I had just discovered were things said by Yogi Berra, the baseball player. My son wrote back: You mean Yogi Bear, don’t you? My son is in his 50s (and that sounds horrible because it puts me 20-some years ahead of him). I wrote back and explained that, no, I did not mean Yogi Bear. He had never heard of Yogi Berra.

Yogi Bear made his television debut in 1958; Yogi Berra had made his baseball debut in 1946, and by the time the cartoon character hit the screens, the baseball player was a household name. That would

Yogi Bear made his television debut in 1958; Yogi Berra had made his baseball debut in 1946, and by the time the cartoon character hit the screens, the baseball player was a household name. That would  explain why people in my generation (born in the United States) would have heard of Yogi Berra. According to Wikipedia, Berra sued Bear (Hanna-Barbera Cartoons) for defamation, but Bear cried coincidence and Berra ended up dropping the suit. As Berra quipped afterwards: “Half the lies they tell about me aren’t true”, to which Bear would have answered: “I’m smarter than the av-er-age bear!” just so people would know who had won that argument.

explain why people in my generation (born in the United States) would have heard of Yogi Berra. According to Wikipedia, Berra sued Bear (Hanna-Barbera Cartoons) for defamation, but Bear cried coincidence and Berra ended up dropping the suit. As Berra quipped afterwards: “Half the lies they tell about me aren’t true”, to which Bear would have answered: “I’m smarter than the av-er-age bear!” just so people would know who had won that argument.

Another coincidence, as long as we are on that theme (that is where we are, isn’t it?): both Yogis, Berra and Bear, lived in Parks. Berra lived in baseball parks and Bear lived in ‘Jellystone Park’. So if one day in the 60s you happened to be in the USofA and you said offhand to someone: I’m going to the park to see Yogi, you’d have no idea what image ran through the other’s head!

Another coincidence, as long as we are on that theme (that is where we are, isn’t it?): both Yogis, Berra and Bear, lived in Parks. Berra lived in baseball parks and Bear lived in ‘Jellystone Park’. So if one day in the 60s you happened to be in the USofA and you said offhand to someone: I’m going to the park to see Yogi, you’d have no idea what image ran through the other’s head! Just how far the Generation Gap can go was proven in September of last year when the Associated Press reported the death of Hanna-Barbera’s animated character, Yogi Bear who, they went on to comment, ‘was also a Hall-Of-Fame catcher with the Yankees’. The headline reads

Just how far the Generation Gap can go was proven in September of last year when the Associated Press reported the death of Hanna-Barbera’s animated character, Yogi Bear who, they went on to comment, ‘was also a Hall-Of-Fame catcher with the Yankees’. The headline reads Yogi Berra once said: “If you don’t know where you are going, you’ll end up someplace else”, and I guess he knew what he was talking about because today everyone thinks he still lives in Jellystone Park and he didn’t even know he was playing there.

Yogi Berra once said: “If you don’t know where you are going, you’ll end up someplace else”, and I guess he knew what he was talking about because today everyone thinks he still lives in Jellystone Park and he didn’t even know he was playing there.

after a few false starts, I came to a dead stop and haven’t been able to write anything since. I seemed to have lost the way to Inspiration.

after a few false starts, I came to a dead stop and haven’t been able to write anything since. I seemed to have lost the way to Inspiration. pretended for a while that a fork in the road is nothing but that: just a fork in the road. Still there was no going forward.

pretended for a while that a fork in the road is nothing but that: just a fork in the road. Still there was no going forward. Well, I guess not, because in spite of the walks and in spite of doing exercise three times a week with my personal trainer, in spite of my morning coffee with friends and my progress in speaking French, in spite of reading through volumes 1 and 2 of the Century trilogy by Ken Follet (in hopes of finding inspiration)and beating the computer’s best player at Scrabble I was not happy.

Well, I guess not, because in spite of the walks and in spite of doing exercise three times a week with my personal trainer, in spite of my morning coffee with friends and my progress in speaking French, in spite of reading through volumes 1 and 2 of the Century trilogy by Ken Follet (in hopes of finding inspiration)and beating the computer’s best player at Scrabble I was not happy. quote from Yogi Berra. It said, in no uncertain terms: “IF YOU COME TO A FORK IN THE ROAD, TAKE IT,” and I was blown away. During the two days it has taken me to finish the series and decide to go cold-turkey on not starting another one; in the 48 hours it has taken me to limit my game-playing to early morning wake-up hours and just before bed finishing-the-day time, the phrase has repeated

quote from Yogi Berra. It said, in no uncertain terms: “IF YOU COME TO A FORK IN THE ROAD, TAKE IT,” and I was blown away. During the two days it has taken me to finish the series and decide to go cold-turkey on not starting another one; in the 48 hours it has taken me to limit my game-playing to early morning wake-up hours and just before bed finishing-the-day time, the phrase has repeated  10 zillion times in my brain: “If you come to a fork in the road, take it”. So that is exactly what I have done!

10 zillion times in my brain: “If you come to a fork in the road, take it”. So that is exactly what I have done!

cake, that’s selfish of you.” “You never think of anyone else… you’re so selfish.”

cake, that’s selfish of you.” “You never think of anyone else… you’re so selfish.”

cafeteria (which meant, market for the coffee service, make sure everything was washed up and put away after each meeting and serve coffee to newcomers). Somehow, this sounded just like what I had done during all the years of my marriage and finally, I balked.

cafeteria (which meant, market for the coffee service, make sure everything was washed up and put away after each meeting and serve coffee to newcomers). Somehow, this sounded just like what I had done during all the years of my marriage and finally, I balked. men and that the program had been made for men based on a religion that was basically paternalistic. Men, with women taking care of them, beginning with Mother, then Wife, then Daughter, had developed quite an ego. Women, I believed then, had not developed an “ego” (at least, I thought that I hadn’t), we had not learned to say: I, I, I, me, me, me. So I set about developing my own ego (I was 50, mind you) which in my mind was: learning how to be selfish.

men and that the program had been made for men based on a religion that was basically paternalistic. Men, with women taking care of them, beginning with Mother, then Wife, then Daughter, had developed quite an ego. Women, I believed then, had not developed an “ego” (at least, I thought that I hadn’t), we had not learned to say: I, I, I, me, me, me. So I set about developing my own ego (I was 50, mind you) which in my mind was: learning how to be selfish. whatever you want. What I discovered was that I didn’t even know what my wants and desires, my likes and dislikes were. I didn’t have the habit of asking myself anything! I was accustomed to ask other people: Where do you want to go? What movie do you want to see? What would you like to eat? But… ah yes, there was a big BUT… I expected other people to think of me first, know instinctively what I wanted, and choose for me. Now if that’s not a Lose-Lose proposal, I’ve never seen one! Fastlane to frustration!

whatever you want. What I discovered was that I didn’t even know what my wants and desires, my likes and dislikes were. I didn’t have the habit of asking myself anything! I was accustomed to ask other people: Where do you want to go? What movie do you want to see? What would you like to eat? But… ah yes, there was a big BUT… I expected other people to think of me first, know instinctively what I wanted, and choose for me. Now if that’s not a Lose-Lose proposal, I’ve never seen one! Fastlane to frustration! What movie were you thinking of?

What movie were you thinking of? After about a week or so during which I really checked with myself every time there was a choice, I discovered that I did have likes and dislikes and that some of them were very definite. I also found that when I knew what I wanted it wasn’t so hard to get it for myself or to convince the other to give it to me. I also found that when I had satisfied myself with what I had chosen one time, it was easier and felt better letting the other person have what they wanted the next.

After about a week or so during which I really checked with myself every time there was a choice, I discovered that I did have likes and dislikes and that some of them were very definite. I also found that when I knew what I wanted it wasn’t so hard to get it for myself or to convince the other to give it to me. I also found that when I had satisfied myself with what I had chosen one time, it was easier and felt better letting the other person have what they wanted the next. when the whim hit me; watched the movies I enjoyed, left the room and went to read a book elsewhere if I didn’t… I was unflinchingly selfish in every possible way, determined to grow a good (male) ego before facing the inevitable chore of undoing it.

when the whim hit me; watched the movies I enjoyed, left the room and went to read a book elsewhere if I didn’t… I was unflinchingly selfish in every possible way, determined to grow a good (male) ego before facing the inevitable chore of undoing it. versa).

versa). prerogative. Being responsible for my wants and likes and giving them to myself whenever possible, also opened me to the unexpected pleasure of being unselfish whenever I felt like it, something that suddenly was much more frequent than before.

prerogative. Being responsible for my wants and likes and giving them to myself whenever possible, also opened me to the unexpected pleasure of being unselfish whenever I felt like it, something that suddenly was much more frequent than before. I stood for a moment looking into his eyes and then a very wide smile crept over my face.

I stood for a moment looking into his eyes and then a very wide smile crept over my face. In the spring of 1616, William Shakespeare died. He was 52 years old. Although most of his work had already been published in editions of questionable quality, it wasn’t until 1623 that two of his friends and fellow actors finally published a more definitive text called the First Folio. In the preface, Shakespeare was hailed as “not of an age, but for all time”. Today, his complete works are free on Internet and few of us have not been touched by Shakespeare; I for one have so often been amazed at the depth of his knowledge of the human mind and heart as to be convinced that after William, there is nothing new under the sun. So many things that modern psychology has allowed us to see, he already knew. I recently quoted him in relation to my work with the method of Byron Katie: “There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so” (Hamlet, Act II, Scene II) and his phrases have become so commonplace that we no longer remember they came from him. “It’s Greek to me”, “In my mind’s eye”, “Can one desire too much of a good thing”, “Forever and a day”, “But love is blind”, “The world’s mine oyster”, “As good luck would have it”, “He will give the devil his due”, “I’ll not budge an inch”, “I have not slept a wink”, “Out of the jaws of death”, “The game is up” and so forth. Shakespeare is so much a part of our everyday language that it is hard to believe anyone could find fault with him, yet the Puritans did along with theater as a whole. The Puritans, it seems could find fault with almost anything that was entertaining, exciting or just downright distracting except –that is- sex… as long as it was practiced within marriage (and with your partner, of course).

In the spring of 1616, William Shakespeare died. He was 52 years old. Although most of his work had already been published in editions of questionable quality, it wasn’t until 1623 that two of his friends and fellow actors finally published a more definitive text called the First Folio. In the preface, Shakespeare was hailed as “not of an age, but for all time”. Today, his complete works are free on Internet and few of us have not been touched by Shakespeare; I for one have so often been amazed at the depth of his knowledge of the human mind and heart as to be convinced that after William, there is nothing new under the sun. So many things that modern psychology has allowed us to see, he already knew. I recently quoted him in relation to my work with the method of Byron Katie: “There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so” (Hamlet, Act II, Scene II) and his phrases have become so commonplace that we no longer remember they came from him. “It’s Greek to me”, “In my mind’s eye”, “Can one desire too much of a good thing”, “Forever and a day”, “But love is blind”, “The world’s mine oyster”, “As good luck would have it”, “He will give the devil his due”, “I’ll not budge an inch”, “I have not slept a wink”, “Out of the jaws of death”, “The game is up” and so forth. Shakespeare is so much a part of our everyday language that it is hard to believe anyone could find fault with him, yet the Puritans did along with theater as a whole. The Puritans, it seems could find fault with almost anything that was entertaining, exciting or just downright distracting except –that is- sex… as long as it was practiced within marriage (and with your partner, of course). In part, the problem was that the theater had grown out of a tradition of enacting religious dramas that was popular amongst Catholics so for the Puritans, who rejected every physical representation of the Divine, it would be suspect from the very beginning. Theaters, public houses, halls where music was played and dancing encouraged were all places that invited vice, drunkenness, gambling and prostitution. Above all, they implied having fun, and fun was considered a dire distraction from the building of a better and more moral society, the only worthy goal here on Earth. Preachers complained that their flock could sit through a couple of hours of theatre and then fall asleep during a one hour sermon. Actors were to be “taken as rogues”, and plays were described as being ‘sucked out of the Devil’s teats, to nourish us in idolatry, heathenry and sin’.

In part, the problem was that the theater had grown out of a tradition of enacting religious dramas that was popular amongst Catholics so for the Puritans, who rejected every physical representation of the Divine, it would be suspect from the very beginning. Theaters, public houses, halls where music was played and dancing encouraged were all places that invited vice, drunkenness, gambling and prostitution. Above all, they implied having fun, and fun was considered a dire distraction from the building of a better and more moral society, the only worthy goal here on Earth. Preachers complained that their flock could sit through a couple of hours of theatre and then fall asleep during a one hour sermon. Actors were to be “taken as rogues”, and plays were described as being ‘sucked out of the Devil’s teats, to nourish us in idolatry, heathenry and sin’. Puritans, and therefore Elizabeth, were brought up reading the Bible, not Shakespeare; she would have been instructed to take every word of the sacred book literally, never doubting that there were snakes in Paradise as surely as there were in Hadleigh. She was shown to avoid wearing colorful clothing or using adornments of any kind –even buttons- which were considered expressions of self-pride, a dreadful sin in itself. She wasn’t allowed to dance, heaven forbid! and the only music to be heard was in church. If she had ever questioned these Spartan rules, which is very doubtful, her father surely would have explained that these earthy occupations excited the imagination and sometimes the body and could do no good for a young woman entering her adulthood. Elizabeth might have thought that having her imagination excited sounded rather… exciting and that her parents seemed to have a peculiar dread of young girls enjoying themselves. Could it possibly be true that all that seemed delightfully enticing was no more than “a waste of time that spent the soul in frivolous pursuits” as her father, no doubt, had emphatically pointed out.

Puritans, and therefore Elizabeth, were brought up reading the Bible, not Shakespeare; she would have been instructed to take every word of the sacred book literally, never doubting that there were snakes in Paradise as surely as there were in Hadleigh. She was shown to avoid wearing colorful clothing or using adornments of any kind –even buttons- which were considered expressions of self-pride, a dreadful sin in itself. She wasn’t allowed to dance, heaven forbid! and the only music to be heard was in church. If she had ever questioned these Spartan rules, which is very doubtful, her father surely would have explained that these earthy occupations excited the imagination and sometimes the body and could do no good for a young woman entering her adulthood. Elizabeth might have thought that having her imagination excited sounded rather… exciting and that her parents seemed to have a peculiar dread of young girls enjoying themselves. Could it possibly be true that all that seemed delightfully enticing was no more than “a waste of time that spent the soul in frivolous pursuits” as her father, no doubt, had emphatically pointed out. In 1620, Elizabeth turned 18. On the 6th of September of that year, the Mayflower sailed for the New World with 102 passengers and 30 more between officers and crew, but probably no one in Hadleigh heard about it or cared for that matter. It may seem strange for us to think today that such a signal event could be totally ignored at the time but that is how history is: we go about our daily lives ignorant of the fact that someone in the future will either make up a story about how important we were or pass us over entirely.

In 1620, Elizabeth turned 18. On the 6th of September of that year, the Mayflower sailed for the New World with 102 passengers and 30 more between officers and crew, but probably no one in Hadleigh heard about it or cared for that matter. It may seem strange for us to think today that such a signal event could be totally ignored at the time but that is how history is: we go about our daily lives ignorant of the fact that someone in the future will either make up a story about how important we were or pass us over entirely. Elizabeth, apparently in no hurry to wed, sat out the year without a beau. The Mayflower, on the other hand, hurried to its destination arriving around the middle of November after a gruelling journey. They had been lucky: only two passengers had died during the crossing. They were not, however, to fare as well during their first winter which turned out to be an extremely harsh one. Obliged to sit it out aboard the ship, the 100 surviving passengers found themselves decimated by disease; a combination of pneumonia, scurvy and tuberculosis left only 54 passengers and 15 crew members to

Elizabeth, apparently in no hurry to wed, sat out the year without a beau. The Mayflower, on the other hand, hurried to its destination arriving around the middle of November after a gruelling journey. They had been lucky: only two passengers had died during the crossing. They were not, however, to fare as well during their first winter which turned out to be an extremely harsh one. Obliged to sit it out aboard the ship, the 100 surviving passengers found themselves decimated by disease; a combination of pneumonia, scurvy and tuberculosis left only 54 passengers and 15 crew members to disembark the following spring. Those are numbers; they sound dire, but they don’t tell us anything about the families that made the voyage, about the mothers that watched their children die and could do nothing about it, of the children who lost their parents, of the men who stood helpless as their wives succumbed to disease or starvation. Numbers don’t speak of pain or sacrifice; they are just finger-counts of tragedy. And even more sad, the names of those that died were not remembered as the new settlers founded the future Nation.

disembark the following spring. Those are numbers; they sound dire, but they don’t tell us anything about the families that made the voyage, about the mothers that watched their children die and could do nothing about it, of the children who lost their parents, of the men who stood helpless as their wives succumbed to disease or starvation. Numbers don’t speak of pain or sacrifice; they are just finger-counts of tragedy. And even more sad, the names of those that died were not remembered as the new settlers founded the future Nation. It must have been sometime between the end of 1623 and the beginning of 1624 when Elizabeth Smyth met Samuel Smyth from Whatfield, a somewhat smaller village lying some two miles north of Hadleigh. If these two young lovers had lived in Spain where children kept both parents names, their offspring would have been Smyth and Smyth, and heaven forbid any of them should also have married a Smith of whom there were myriads, much to the dismay of future genealogists. Fortunately, they lived in England, so Miss Elizabeth Smyth became Mrs Elizabeth Smyth without even having to change her signature.

It must have been sometime between the end of 1623 and the beginning of 1624 when Elizabeth Smyth met Samuel Smyth from Whatfield, a somewhat smaller village lying some two miles north of Hadleigh. If these two young lovers had lived in Spain where children kept both parents names, their offspring would have been Smyth and Smyth, and heaven forbid any of them should also have married a Smith of whom there were myriads, much to the dismay of future genealogists. Fortunately, they lived in England, so Miss Elizabeth Smyth became Mrs Elizabeth Smyth without even having to change her signature. Samuel Smyth, like his father before him, was a fellmonger, a dealer in hides and sheepskins which he prepared for tanning. Exactly when Elizabeth began to notice him, or him her is not known at all and much less for sure. They might have seen each other in the Hadleigh marketplace or in church, or strolling along High Street, and perhaps Samuel, after seeing la belle Elizabeth spoke to his father who in turn would speak to Elizabeth’s father who in turn would speak to his wife who would in turn speak to her, or the other way around, but what is known for certain, without the smallest doubt and absolutely, is that by May of 1624 they knew each other quite well. I will refrain from wondering if this levity

Samuel Smyth, like his father before him, was a fellmonger, a dealer in hides and sheepskins which he prepared for tanning. Exactly when Elizabeth began to notice him, or him her is not known at all and much less for sure. They might have seen each other in the Hadleigh marketplace or in church, or strolling along High Street, and perhaps Samuel, after seeing la belle Elizabeth spoke to his father who in turn would speak to Elizabeth’s father who in turn would speak to his wife who would in turn speak to her, or the other way around, but what is known for certain, without the smallest doubt and absolutely, is that by May of 1624 they knew each other quite well. I will refrain from wondering if this levity  of morals was passed down through the generations for I consider that each generation is responsible for its own, shall we say, de-generation.

of morals was passed down through the generations for I consider that each generation is responsible for its own, shall we say, de-generation. “full”, so to speak, in order to cover any untimely fullness there might be underneath. However that may be, in Elizabeth’s case appearances were kept, at least until the following year when little Samuel was born on February 7th, just four months after the ceremony.

“full”, so to speak, in order to cover any untimely fullness there might be underneath. However that may be, in Elizabeth’s case appearances were kept, at least until the following year when little Samuel was born on February 7th, just four months after the ceremony. Yet all was not conjugal bliss and family; there was “double, double toil and trouble,” in more than just Shakespeare’s Macbeth, as the Century of the General Crisis became each year more worthy of its name.

Yet all was not conjugal bliss and family; there was “double, double toil and trouble,” in more than just Shakespeare’s Macbeth, as the Century of the General Crisis became each year more worthy of its name. Meet my Best Friend and my own True Love. She is someone (or something) that has been with me from the moment of my conception and will continue with me until dust do us part. She is less than a heartbeat away and nearer than the breath that joins us. She has been there during every single experience, both conscious and unconscious, and she lets me know the instant anything goes wrong (when a finger gets too close to the fire or a toe meets a table leg, or my mind is conjuring up a terrifying nightmare).

Meet my Best Friend and my own True Love. She is someone (or something) that has been with me from the moment of my conception and will continue with me until dust do us part. She is less than a heartbeat away and nearer than the breath that joins us. She has been there during every single experience, both conscious and unconscious, and she lets me know the instant anything goes wrong (when a finger gets too close to the fire or a toe meets a table leg, or my mind is conjuring up a terrifying nightmare). le should look like, and soon –if not already- she will begin the opposite process until once more becoming minuscule and disappearing. I know that you’ve guessed by now that I am talking about My Body. Hmmm, is it mine? Perhaps, in the sense that a rented car is ‘mine’ as long as I have the use of it and then goes back to being agency property when I am through. Therefore, it is my ‘Best Friend and own True Love’

le should look like, and soon –if not already- she will begin the opposite process until once more becoming minuscule and disappearing. I know that you’ve guessed by now that I am talking about My Body. Hmmm, is it mine? Perhaps, in the sense that a rented car is ‘mine’ as long as I have the use of it and then goes back to being agency property when I am through. Therefore, it is my ‘Best Friend and own True Love’  on loan.

on loan. (and was made to wash her own sheets); she wet the beds in every hotel she stayed in and even in her grandmother’s house when we slept over. My Body turned 7 and 8 and 9 and 10 and continued wetting the bed. We moved to Mexico and turned 11 and she still insisted on emptying her bladder as soon as deep sleep moved in.

(and was made to wash her own sheets); she wet the beds in every hotel she stayed in and even in her grandmother’s house when we slept over. My Body turned 7 and 8 and 9 and 10 and continued wetting the bed. We moved to Mexico and turned 11 and she still insisted on emptying her bladder as soon as deep sleep moved in. an alarm clock that would wake the dead, and a set of instructions of how to plug the whole thing into the lights in the room. That night My Body was introduced to its executioner. Of course, by that time she had been peeing in bed almost every night for about 5 years and I didn’t think there was anything that could stop her. We were both in for a surprise.

an alarm clock that would wake the dead, and a set of instructions of how to plug the whole thing into the lights in the room. That night My Body was introduced to its executioner. Of course, by that time she had been peeing in bed almost every night for about 5 years and I didn’t think there was anything that could stop her. We were both in for a surprise. gave My Body an electric shock that sprang her out of sleep and convinced her that if she continued in that direction she would be electrocuted; it set off the alarm that woke my parents in another bedroom and probably the neighbors, and all the lights in the room went on.

gave My Body an electric shock that sprang her out of sleep and convinced her that if she continued in that direction she would be electrocuted; it set off the alarm that woke my parents in another bedroom and probably the neighbors, and all the lights in the room went on. However, five years at the mercy of My Body’s shameless behavior had taught me not only a total mistrust of the traitor, but also that I was completely powerless over her: she was going to do what she was going to do whether I liked it or not. That meant future endless torture especially in my teen years: an oversized bottom half with an undersized top endowment; pimples always in very visible places and right when there was a big dance or party to be attended; a frame made for a taller woman thanks to one leg that insisted on growing faster and had to be stopped; a nose that in boarding school earned me the

However, five years at the mercy of My Body’s shameless behavior had taught me not only a total mistrust of the traitor, but also that I was completely powerless over her: she was going to do what she was going to do whether I liked it or not. That meant future endless torture especially in my teen years: an oversized bottom half with an undersized top endowment; pimples always in very visible places and right when there was a big dance or party to be attended; a frame made for a taller woman thanks to one leg that insisted on growing faster and had to be stopped; a nose that in boarding school earned me the  nickname of Dome; a mother that was to me the most beautiful and perfect woman ever created; and a grandmother that said “round eyes, round nose, round face” every time she looked at me and, when I was 18, suggested I have my nose fixed (by that time I was arrogant enough to respond: “It gives me personality” and not do it).

nickname of Dome; a mother that was to me the most beautiful and perfect woman ever created; and a grandmother that said “round eyes, round nose, round face” every time she looked at me and, when I was 18, suggested I have my nose fixed (by that time I was arrogant enough to respond: “It gives me personality” and not do it). where that led me and I am not going into it again!

where that led me and I am not going into it again! realized that if I didn’t start appreciating the beauty that she did have, instead of thinking she should have a different kind of

realized that if I didn’t start appreciating the beauty that she did have, instead of thinking she should have a different kind of  beauty, more like her mother’s for instance, I would some day in the future look back and realize how attractive I had been at that moment. It was then I knew that I had to accept My Body for what it was and make the best of it.

beauty, more like her mother’s for instance, I would some day in the future look back and realize how attractive I had been at that moment. It was then I knew that I had to accept My Body for what it was and make the best of it. helpfulness, honesty, kindness, etc. And every day I would stand in my dressing-room contemplating the pictures of My Body and finding her more and more acceptable. I did not, however, love her.

helpfulness, honesty, kindness, etc. And every day I would stand in my dressing-room contemplating the pictures of My Body and finding her more and more acceptable. I did not, however, love her. treat My Body at least half as lovingly as I treated my dog’s body. How could I love her body and not mine, when her body never even looked for mine unless she wanted something, and mine had been at my beck and call every second of every day since the beginning of my time? I understood the injustice I had committed and I looked down at My Body for the first time with tenderness, the same kind of tenderness that Salomé’s body had awakened in me.

treat My Body at least half as lovingly as I treated my dog’s body. How could I love her body and not mine, when her body never even looked for mine unless she wanted something, and mine had been at my beck and call every second of every day since the beginning of my time? I understood the injustice I had committed and I looked down at My Body for the first time with tenderness, the same kind of tenderness that Salomé’s body had awakened in me.

flows over me that I smile and hug My Body, and tell her that she’s doing fine, that we’re doing just fine.

flows over me that I smile and hug My Body, and tell her that she’s doing fine, that we’re doing just fine.